I've been aware of the potential of Google Docs for

collaboration for quite a while but I had never really considered the use of

Google Docs for classroom activities. That is, until a few weeks

ago...

I run a final-year undergraduate module called Building

Adaptation and Conservation, in which students are required to consider the

adaptive reuse of historic buildings. The students are generally well

engaged and fairly opinionated, which makes the module enjoyable because the

subject lends itself to a lot of discussion.

I wanted to run a class exercise in which students work in

groups to discuss the preparation of a conservation plan. I gave a

lecture in which I explained the purpose of conservation plans and identified

the key components of such a plan. In previous years when I have run a similar

exercise, students formed themselves into groups, discussed the topic, made

notes within their group and then fed back to a plenary session. There was no

formal capture of the outcomes of these discussions.

It occurred to me that Google Docs could provide a means of

addressing this problem. I knew there would be a maximum of fifteen groups in

the session, so beforehand I created fifteen documents in Google Docs which

were identical apart from the document heading, which simply indicated a group

number. I then created a separate link to each Google Doc from within

Blackboard (our virtual learning environment) and made these links available to

all students on the module. I also made some example conservation plans

available to the students via Blackboard. I asked students in advance to bring

devices with them to the session from which they could access the

internet.

I presented a case study based on a real Georgian building

in central London. I outlined some of the key features of the building and

showed the students a series of photographs. Once they had formed their groups

I allocated a number to each group by simply giving the group a slip of paper

with a number on it. Each group then had to access a specific Google Doc on

Blackboard and add information to the document.

Specifically, I asked each

group to consider:

- How would you go about preparing the conservation plan?

- What information would go in to the conservation plan?

- What format would the conservation plan be in?

- How could you present information in a way which can be understood?

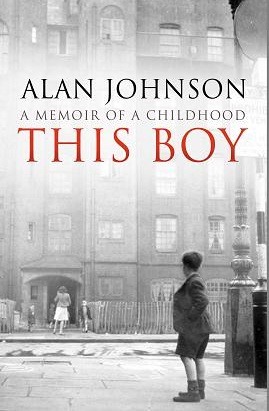

Screenshot from Blackboard showing access to Google Docs

The students appeared to engage quite well with the

exercise. They were able to access Google Docs on a variety of devices

including laptops, tablets and smart phones. Once the exercise was complete I

was able to open individual group documents on the screen at the front and talk

through some of the issues identified.

The advantages of using Google Docs were as follows:

- Groups had a ready-made template in which to enter the outcomes of their discussion immediately.

- Individual members of each group could all add information to the document simultaneously as long as they had a suitable device with them.

- Once the exercise was complete all members of the group had equal access to the document they had prepared.

- All students had access to the documents produced by other groups, thus enabling them to benefit from the input of the entire class.

I think this worked rather well as a means of capturing the

discussions, and was much better than students simply writing their ideas down

on a piece of paper and not really sharing that with anyone else.

I'll be using this approach again.